Push hands is an accessible abstraction of fighting. Whereas mortal combat follows no pattern and honors no rules, the push hands exercise is relatively limited in scope. Push hands practice alone will not make a top fighter, nor is it intended to do so; it focuses on specific characteristics, such as sticking and following, in order to provide a consistent and effective learning environment.

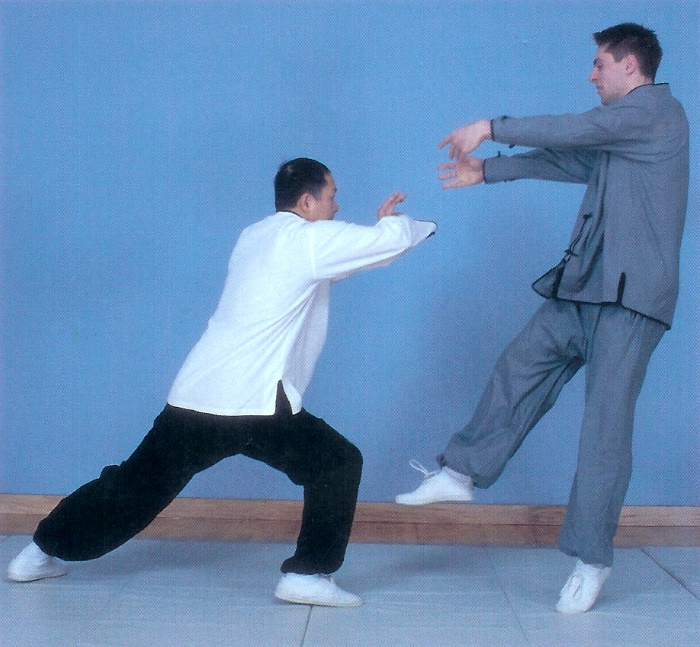

Yang Jwing-Ming demonstrates Press (Ji)

Abstractions such as the fixed step tui shou exercise are often misused, by students who do not fully understand their context within the larger Tai Chi curriculum. These students shape the exercise into something more or less than it is intended to be, diminishing its relevance and benefits, and shortchanging themselves and their training partners.

What should the pushing hands drill include, and what should it exclude? We can start our investigation with the written guidelines of past masters.

From “Song of Pushing Hands” (translated by Yang Jwing-Ming)

Be conscientious about Wardoff (Peng), Rollback (Lu), Press (Lu), and Push (An). Up and down follow each other, (then) the opponent (will find it) difficult to enter.

No matter (if) he uses enormous power to attack me, (I) use four ounces to lead (him aside), deflecting (his) one thousand pounds. Guide (his power) to enter into emptiness, then immediately attack; Adhere-Connect, Stick-Follow, do not lose him.

From “Taijiquan Classic” by Wang Zong-Yue

…Following the opponent, bend, then extend. When the opponent is hard, I am soft; this is called yielding. When I follow the opponent, this is called sticking.

…There are many martial art styles. Although the postures are distinguishable from one another, after all, it is nothing more than the strong beating the weak, the slow yielding to the fast. The one with power beats the one without power, the slow hands yield to the fast hands. All this is natural born ability. It is not related to the power that has to be learned.

…Fundamentally, give up yourself and follow the opponent.

As pushing hands is an exercise to develop Tai Chi skills, it obviously must not deviate from these core principles of the art. At the same time, we should avoid attributing a false specificity to English translations (creative approximations) of the original Chinese, and follow the spirit rather than the letter of the text.

Most importantly, we should recognize that Tai Chi push hands cannot be fully described in a few paragraphs, and the practice need not be constrained to those specific strategies and techniques listed within.

Push Hands is Not a Form

When push hands training goes astray, it is not necessarily because the Tai Chi principles have been intentionally disregarded. A lack of familiarity with the breadth of partner practice methods, combined with unskillful views on the value of competition result in a wasted opportunity.

At one extreme, push hands is played like a Ouija board, wherein no party accepts responsibility for their influence. The emphasis is placed on creating a perfectly round circle, moving at a perfectly even speed. Such training is perfectly cooperative and perfectly useless.

Taiji: Yin and Yang

When nobody leads, then nobody can learn to follow. When nobody supplies force, then nobody can learn to neutralize it. Push hands players must alternate between these roles to develop true listening and sticking skills. If alternation is suppressed in pursuit of ultimate smoothness, than push hands cannot serve as the intended bridge between solo training and free fighting. Those more peacefully inclined will find that such empty practice also does little or nothing for their self-awareness.

Push Hands is Not Free Sparring

Most of the 36 tui shou “sicknesses” noted by master Chen Xin are grounded in confusion about the difference between push hands and sparring. The carefree, “anything goes” attitude required for freestyle practice cannot be reconciled with in-depth study; if you are doing one, then you are not doing the other.

Chen Xin’s list of bad behaviors—which are valid in sanshou but nevertheless inhibit Tai Chi skill development—includes:

- Breaking contact to escape an attack

- Grabbing and holding the opponent to restrict their movement

- Sneak attacks (e.g. “Your shoelaces are untied”)

- Pushing the opponent away without first establishing control

- Stiffening up to avoid being moved

- Using strength to lift the opponent up

Other times, the problem is not confusion, but frustration felt by a player who is technically outclassed. To avoid further humiliation, they attempt to change the rules in their favor. This is just a further obfuscation of the sneak attack, with little educational value. As Xiang Kairen explains:

In the past, I had studied external boxing; sometimes I would get aggravated by Master Liu’s attack and use external boxing methods to strike. He would immediately stop pushing and say, “Push-hands is a method of training; it is not fighting. Your mind must not be struggling with the thoughts of winning or losing. If we were comparing our abilities in competition, then our postures would not be the same. There would be no principle of standing without moving or waiting for your partner to attack.

When I heard these words, I was very ashamed. I had a deep sense that, while pushing hands, I should harbor no thought of winning or losing. Not abiding by the rules and trying to steal a hit is what martial artists call “breaking tradition.” In social intercourse, my actions would be called “lack of courtesy”. Essentially I was being immoral.

The Role of Competition

These examples show how both the elevation, and the complete exclusion of competitive behavior devalue pushing hands. How can we identify the ideal middle ground?

Just a note on your caption, Press is “Ji”, rollback is “Lu”. Thanks for empahsizing that push hands is training, not fighting.

How embarassing! Thanks for catching that.

“Just the Facts, ma’am!”

1) The ‘song’ referenced is not Song of Pushing Hands. It’s Song of Hitting Hands. It’s about San Shou not Push Hands.

2) The statement, “Push hands is an accessible abstraction of fighting.” Is wrong. It is not. Push Hands IS a vehicle to teach us TiFang (AKA: The technique of: Attract into emptiness, join, and discharge; alternate pushing and pulling to sever the root so the other can be thrown out decisively; four ounces offsets 1000 lbs).

I do agree with the following, 100%:

…while pushing hands, I should harbor no thought of winning or losing. Not abiding by the rules and trying to steal a hit….

This translation was chosen by Yang Jwing-Ming, Ph.D. You say he got it wrong? Dr. Yang and I respectfully disagree.

Hi Chris,

Respectfully, two points:

First, we do a little dictionary work…

打 – dǎ — To beat / to strike / to hit / to break / to type / to mix up / to build / to fight / to fetch / to make / to tie up / to issue / to shoot / to calculate / to play (a game) / since / from.

No “push” in there.

Second, the line 任他巨力來打我, is translated above as: “No matter (if) he uses enormous power to attack me”; here, 打 is translated loosely as “attack”. My translation: “Let him come and hit with great strength”

No “push” there.

The error? Translating a word in two different ways, less then 25 characters apart; and, shoe-horning a translation to make it fit what you want it to say. We ‘want’ it to be The Song of Push Hands because the first 4 words of the first line are a list of the postures of Push Hands. But, that is not what the Chinese says (打手歌).

Regards,

Stephen : )

That is not an error, Stephen. It’s the difference between a professionally executed, context-aware translation and a dictionary check.

The reference to “four ounces” immediately contextualizes the surrounding advice for a gentleman’s parlor game, i.e. pushing hands. As opposed to combat sport, sanshou, self-defense or street crime.

Hi Chris.

No, both your points are incorrect.

Thank you,

Stephen